(This is the third posting in our series on “Quantifying Inefficiency: Comparing Comparisons,” and it is encouraged that they be read in sequence: Part I, Part II.)

In Part I of our blog series on “Quantifying Inefficiency: Comparing Comparisons,” we introduced the fundamentals of inefficiency and detailed the most reliable way of analyzing and quantifying the impact that work performed inefficiently can have on a construction project: the measured mile analysis. However, we also explained that the measured mile analysis requires both an “impacted” and “unimpacted” period on the same project. In cases where that does not exist, the next approach is to compare the actual productivity achieved on the project in question to another, similar project that was performed previously.

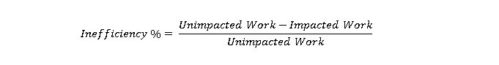

In Part II of this blog series, we laid out the approach of comparing the impacted productivity experienced on the current project to that of an unimpacted productivity experienced on a past project. As part of this analysis approach, it is incumbent on the analyst to use actual productivities achieved on a previous project that is as similar as possible to the impacted project to minimize productivity loss that may be attributable to factors not related to the impact or impacts on the current project. In either approach, the quantification of the inefficiency percentage experienced by a contractor is as follows:

![]()

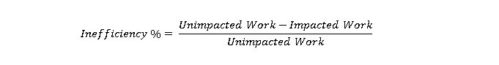

In Part I of our blog series on “Quantifying Inefficiency: Comparing Comparisons,” we introduced the fundamentals of inefficiency and detailed the most reliable way of analyzing and quantifying the impact that work performed inefficiently can have on a construction project: the measured mile analysis. As discussed in Part I, the measured mile analysis compares the productivity in an unimpacted period of performance and an impacted period of performance of the same operation to quantify the contractor’s inefficiency using the simple formula below:

In Part I of our blog series on “Quantifying Inefficiency: Comparing Comparisons,” we introduced the fundamentals of inefficiency and detailed the most reliable way of analyzing and quantifying the impact that work performed inefficiently can have on a construction project: the measured mile analysis. As discussed in Part I, the measured mile analysis compares the productivity in an unimpacted period of performance and an impacted period of performance of the same operation to quantify the contractor’s inefficiency using the simple formula below:

However, when an impacted project has no period of performance that can be classified as unimpacted or nearly unimpacted, then there is no reliable and easily identifiable “unimpacted” period of performance on that project to use as the baseline period of productivity. Thus, the version of the measured mile analysis described above that uses the “impacted” and “unimpacted” periods of performance from the same project cannot be used to accurately quantify the contractor’s inefficiency. This is because the formula in this scenario, by relying on the achieved productivity of the same operation on the same project, in most cases will underestimate the contractor’s lost productivity.

Consider the following example. Project A, originally planned to begin in late summer with site excavation work, has its notice-to-proceed (NTP)

As discussed in the introductory post to this series on inefficiency, when a contractor’s operation experiences a reduction in productivity the result is usually the expenditure of more labor and/or equipment hours than it originally estimated. These additional labor and/or equipment hours, in turn, can result in significant losses that will negatively affect a contractor’s profitability. Often, the impacts responsible for contractor’s inefficiency were not within its control and, as such, the contractor may be entitled to recover its additional costs resulting from the inefficient operation.

As discussed in the introductory post to this series on inefficiency, when a contractor’s operation experiences a reduction in productivity the result is usually the expenditure of more labor and/or equipment hours than it originally estimated. These additional labor and/or equipment hours, in turn, can result in significant losses that will negatively affect a contractor’s profitability. Often, the impacts responsible for contractor’s inefficiency were not within its control and, as such, the contractor may be entitled to recover its additional costs resulting from the inefficient operation.

The contractor’s ability to recover its additional costs resulting from the inefficient operation can be determined by the contract. If the contract is silent, then typically the contractor would have to determine who or what was responsible for the impact that caused its operation to be inefficient. Typically, if the impact was a force majeure event, then the contractor may not be able to recover additional costs from the owner. However, if the contractor can demonstrate that the impact and its expenditure of additional labor and/or equipment costs was caused by the owner or could be attributable to the owner, then the contractor should be able to recover its additional costs.

However, in order to determine the extent to which its operation was inefficient and to calculate the additional costs that it may be entitled to recover, it is crucial

For contractors, profitability is the utmost concern on most, if not all, projects. Whether or not a contractor is profitable, and just how profitable they are, depends on how they perform in comparison to their bid. One of the most significant portions of a contractor’s bid involves the amount of manhours and, if applicable, equipment hours necessary to complete its scope of work for the project.

To estimate the number of manhours and/or equipment hours that are necessary to complete its scope of work, a contractor must first determine the planned rate of production it believes it is able to achieve. This requires the contractor to calculate how many manhours and/or equipment hours that it needs to expend to complete a specific quantity of work. The contractor will then multiply its planned rate of production across the quantity of work in its scope for the particular project, in order to calculate its budgeted manhours and/or equipment hours to complete said scope of work.

For example, a contractor is building a 200’ long, 4’ high CMU retaining wall. Assuming standard 8”x16” block is being used, the contractor knows that they need at least 900 blocks to construct the wall. The project also requires that the wall be built in 3 workdays. Therefore, the contractor knows it must lay at least 300 blocks per day to accomplish the scope

In our previous Concurrent Delay posts, we defined concurrent delays and described how the identification of concurrent delays depended on the definition of the “critical path.” In this second part of our “How to Identify a Concurrent Delay” series, we will discuss the two different concurrent delay theories.

AACE International’s Recommended Practice No. 29R-03, Forensic Schedule Analysis, identifies these two types of concurrent delay theories as literal concurrency and functional concurrency. The basic difference between the two is the “timing” of the alleged delays. Under the literal concurrency theory, for two delays to be considered concurrent, the alleged delays must delay the project’s critical path and the forecast completion date at “the same time.” Said another way, the two delays must occur simultaneously.

Under the functional concurrency theory, the alleged delays must only delay the project’s critical path within the same analysis time period, which is typically between consecutive schedule updates, and are not required to have actually occurred on the same days.

In terms of quantifying the concurrency of two alleged concurrent delays, a literal concurrency adherent would argue that the project schedule enables the parties to identify the initial critical path work activity on a daily basis, thus enabling the parties to likewise identify the days during the schedule update period when the alleged concurrent delays were literally concurrent. A functional concurrency adherent would argue that

In previous posts, we discussed why owners and contractors often argue for the existence of concurrent delay and how concurrent delay is defined. This post will be the first of two posts that will tackle how to identify a concurrent delay. As detailed in the previous post, in order for two delays to be concurrent and for one delay to negate one party’s responsibility against another’s, the delays must be concurrently critical. This means that both delays must be capable of delaying the project’s completion date.

As such, the first piece to the puzzle in identifying concurrent delays is related to how the “critical path” or “criticality” is defined. It is generally uncommon for construction contracts to define the term “critical path,” and this lack of a contractual definition means that we’re left to industry standard definitions to fill the void. Arguably, there are two industry standard definitions of the critical path: (1) the longest path, and (2) all activities with total float values of zero or less. However, there’s a clear trend that the longest path definition is the more readily accepted definition of the critical path, as the total float value-based definition can sometimes produce unreliable results due to the use of multiple work calendars that show or limit when particular work can occur during the year. Because work calendars identify the available working

As discussed in the previous posting introducing the concept of concurrent

delay, owners and contractors often argue for the existence of concurrent delay

on their construction projects. Sometimes these arguments make sense;

sometimes they don’t. Most times there is a lot of money at stake in the form

of delay damages. These delay damages include the

contractor’s extended general conditions and unabsorbed home office overhead

costs that might result from an owner-caused delay that delayed the project’s

completion or an owner’s assessment of liquidated damages that might result

from a contractor-caused delay that delayed the project’s completion.

One common mistake is to conclude that concurrent delays need

only be “concurrent” to be significant. In other words, some assume that

simply because the other party’s delay happened as the same time as the delay

you caused, that the other party’s delay negates yours in some way. To be

truly concurrent, however, and to bar on the recovery of delay damages or the

assessment of liquidated damages, the delays have to be more than just

concurrent. Unless the contract provides otherwise (the topic for another

post), the delays also have to be critical.

These days, a well-written construction contract provides clear and complete definition of the critical path. However, even in this day and age, too many construction contracts do not define the critical path. One of the many negative consequences of failing to define that term is that it may enable the parties to make questionable concurrent delay arguments. In essence, it may allow a party to make an argument that a delay that was not critical is

Both contractors and owners often argue for the existence of a concurrent delay to negate the granting of a time extension or payment of delay damages. Concurrent delays are discussed ever more frequently due to the increased cost of construction.

It is essential to understand the concept of concurrent delay when evaluating delays on a construction project. Concurrency is relevant, not just to the identification of critical delays, but, more importantly, to the assignment of the party responsible for the critical project delays. This is due to the fact that the assignment of critical project delay responsibility directly determines whether a time extension should or should not be granted to a contractor and whether one of the parties may owe the other delay-related damages.

An owner may cite the existence of a contractor-caused concurrent delay as a reason for issuing a time extension without additional compensation or even as the reason for not issuing a time extension at all. For example, assume the owner issued a change order adding new scope to a project. If that added work delayed the project’s critical path and the project’s completion date, then the contractor is typically entitled to a time extension equal to the delay caused by the additional work, as well as corresponding delay damages. To avoid granting the contractor a time extension or paying the contractor its resultant delay damages, an owner may argue that the contractor also delayed the project and, as a result, the contractor

Just as contractors incur and are entitled to recover extended general condition and home office costs due to owner-caused project delays, owners likewise incur and are entitled to recover additional and unanticipated management and carrying costs when the contractor delays the project’s completion date.

The owner’s delay damages are represented as either liquidated damages or its actual damages. The reason that owners include a liquidated damages provision in their contracts is due to the fact that it is difficult or practically impossible for owners to accurately determine their actual damages before the contract is executed. Owners rely on liquidated damages to recover a reasonable estimate of the damages that they will incur if the project is delayed by the contractor.

Typically, liquidated damages are calculated at a daily rate. Similar to both extended field overhead and unabsorbed home office overhead, the owner’s recovery of liquidated damages only results from instances when only the contractor causes a critical delay to the project.

Owners should rely on advice from counsel when calculating the appropriate amount of liquidated damages to ensure jurisdictional compliance. However, some of the costs that an owner should consider when preparing an estimate of liquidated damages are as follows:

- Costs for project inspection

- Costs for continued design services

- Costs for the owner’s staff

- Costs for maintaining current or temporary facilities

- Costs for additional rentals

- Costs for additional storage

- Lost revenues

- Costs to the public for not having beneficial use of the facility

- Additional moving expenses

- Costs for escalation

- Costs for financing

More importantly, when a project nears the contract completion date and is