Quantifying Inefficiency: Comparing Comparisons, Part III

(This is the third posting in our series on “Quantifying Inefficiency: Comparing Comparisons,” and it is encouraged that they be read in sequence: Part I, Part II.)

In Part I of our blog series on “Quantifying Inefficiency: Comparing Comparisons,” we introduced the fundamentals of inefficiency and detailed the most reliable way of analyzing and quantifying the impact that work performed inefficiently can have on a construction project: the measured mile analysis. However, we also explained that the measured mile analysis requires both an “impacted” and “unimpacted” period on the same project. In cases where that does not exist, the next approach is to compare the actual productivity achieved on the project in question to another, similar project that was performed previously.

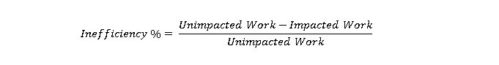

In Part II of this blog series, we laid out the approach of comparing the impacted productivity experienced on the current project to that of an unimpacted productivity experienced on a past project. As part of this analysis approach, it is incumbent on the analyst to use actual productivities achieved on a previous project that is as similar as possible to the impacted project to minimize productivity loss that may be attributable to factors not related to the impact or impacts on the current project. In either approach, the quantification of the inefficiency percentage experienced by a contractor is as follows:

In these situations, the key to the comparisons is that the “unimpacted” or “least impacted” project is sufficiently similar to the “impacted” project. In the case of the measured mile approach, it is exactly the same project, so there are no variables, and in the case of the comparison to previous projects, the past project selected is usually one with many similarities and very few differences. Either way, the analyses are dependent upon a demonstrating that the only variable responsible for the change in productivity is the impact in question, establishing causation that the impact is the true cause of the reduced productivity. If the projects are not similarly situated, the results of the inefficiency analysis comparing productivities may not be reliable without further adjustment.

Consider the following example. On Project A, the contractor alleges that due to a late notice-to-proceed (NTP), it was forced to perform its excavation work during a period of colder and more adverse weather than it originally anticipated and, as such, was only able to excavate 15 cubic yards of soil per day with a four-person crew. Due to the late NTP, the contractor’s excavation operation was affected from the very start of its work so no “unimpacted” portion of the operation existed, and, thus, a measured mile analysis could not be utilized. Instead, the contractor compares its productivity to another excavation project it previously completed during the summer months of the prior year in which the contractor was able to excavate 20 cubic yards of soil per day with the same size crew. The contractor, using the formula above, calculates that this project suffered from a loss of productivity of 25% due to the excavation work being performed during winter months instead of summer months.

However, the contractor’s analysis does not consider that the “unimpacted” project involved the excavation of a sandier soil, while the current, “impacted” project involved wet clay soils, a more difficult soil to excavate. Thus, while the mathematical results of the analysis are still true, the contractor’s statement that the 25% reduction in efficient work is due to the work being performed in winter months may not be accurate. A portion, or even all, of the contractor’s 25% reduction in productivity may be attributable to the current project’s soil conditions being more difficult to excavate. Without accounting for this variable, the contractor’s inefficiency analysis that relies on the unimpacted productivity from a previous project will improperly assign all the reduced productivity to the adverse weather experienced during the winter months.

In situations in which a measured mile analysis cannot be performed and the contractor does not have a similarly situated previous project to rely upon, a third productivity comparison option can be to use the contractor’s bid productivity for its “unimpacted” productivity. As with the comparison to previous projects, while this analysis still utilizes the same formula as the measured mile analysis, strictly speaking it is not a “measured mile” in its purest sense. It is important to note that while the measured mile analysis and the comparison to previous projects analysis are both preferrable, as they rely on “actual, achieved productivities,” to a comparison to the bid, this approach is an acceptable methodology for purposes of calculating lost productivity.

It should also be noted that this approach is not akin to a total cost or modified total cost approach, two methodologies for calculating damages that are generally rebuffed by courts and triers of fact. This approach differs from the total cost and modified total cost approaches in one key way. While those approaches focus on overall costs, which often have several non-labor productivity components like costs of materials, vendors, or subcontractors, the comparison to bid productivity focuses only on productivity, which is a function of labor. Thus, this approach of relying on the contractor’s bid productivity isolates just the labor productivity component of the project and avoids any commingling of other non-labor components that may contaminate the analysis.

Generally speaking, for this approach to be acceptable, it requires some initial groundwork to be laid due to the introduction of variables that did not exist in the previous two approaches and, as such, the analyst should demonstrate several things. First, they should demonstrate that an unimpacted period of productivity does not exist on the current project. Second, they should demonstrate that the contractor does not have a similarly situated previous project that can be used as a basis for the unimpacted productivity. And third, because this comparison relies on bid productivities, they should demonstrate that the bid productivity is reasonable.

While the first two components are rather straightforward to demonstrate, the third, that the contractor’s bid productivity used in the analysis is reasonable, can be difficult. That said, there are a number of ways a contractor can validate its bid for purposes of using in this type of an analysis. For example, the analyst can demonstrate any of the following: that the contractor’s bid was close the other bidders, especially when it comes to labor; that the contractor maintains a bidding software that harnesses historical data from the contractor’s previous projects that serves as the basis for the contractor’s bids; because labor is a function of material, that the contractor’s actual costs for material ended up very closely aligned to its bid material amount; and that the contractor adequately planned for any unique conditions that the current project presented in its bid. While this is certainly not an exhaustive list, establishing these facts can create an accurate and reliable environment for this type of analysis.

Consider our example above. On Project A, the contractor was unable to identify a period of performance in which its work was unimpacted and, while it had performed another project of similar size the summer before, that project had very difficult soil conditions. As a result, the contractor realizes it must rely on its bid for purposes of comparing productivities. The contractor notes that it utilizes sophisticated bidding software that has tracked historical data from all the contractor’s previous projects. It also notes that the next two closest bidders on Project A were within 1.5% of its bid, and the biggest differences between its bid and the next two lowest bidders related to the contractor including a smaller overhead markup. Lastly, the contractor notes that, because it has performed excavations in this geographic location for many years, it understood there would be wet clay soils and, as such, it developed its bid productivity from historical data of projects in the same area that would have experienced similar soils. From all this information, the contractor determined its bid excavation productivity of 18 cubic yards of soil per day per four-person crew.

Thus, when the contractor on Project A is only able to excavate 15 cubic yards of soil per day with the same size crew, the contractor is now able to quantify its lost productivity due to the winter weather conditions because it has validated its bid productivity. As such, using the formula above, the Contractor identifies that its inefficiency percentage due to the winter weather conditions was actually 16.7%.

While calculating lost productivity based on a bid productivity is often criticized as being an apples-to-oranges comparison in that it compares an actual productivity achieved to a theoretical one (the bid), if the analyst can show that the contractor’s bid satisfies some or all of the groundwork discussed above, it ceases to be “theoretical” and becomes more reliable for purposes of quantifying inefficiency. As a result, when a measured mile analysis is unavailable and the contractor lacks a similar previous project to compare to, a comparison to the bid productivity analysis is often a viable alternative to calculating lost productivity due to inefficiency.